As is well known, Napoleon handed himself over to Captain Maitland of the Bellerophon on 15 July 1815. He hoped, as stated in his famous letter to the Prince Regent, that he would be offered asylum in Britain but, to his surprise, was soon shipped off to St Helena, exile and death. Napoleon’s surrender also seems to have come as something of a surprise to those officers of the British navy then blockading France’s western ports, men who included Captain Maitland and his superior, Admiral Hotham, as they had assumed he would make a desperate effort to escape to the United States. News of the surrender would also come as a surprise to British ministers in London and in Paris, for King Louis XVIII had entered Paris on 8 July and Allied officials and dignitaries flowed in in his wake.

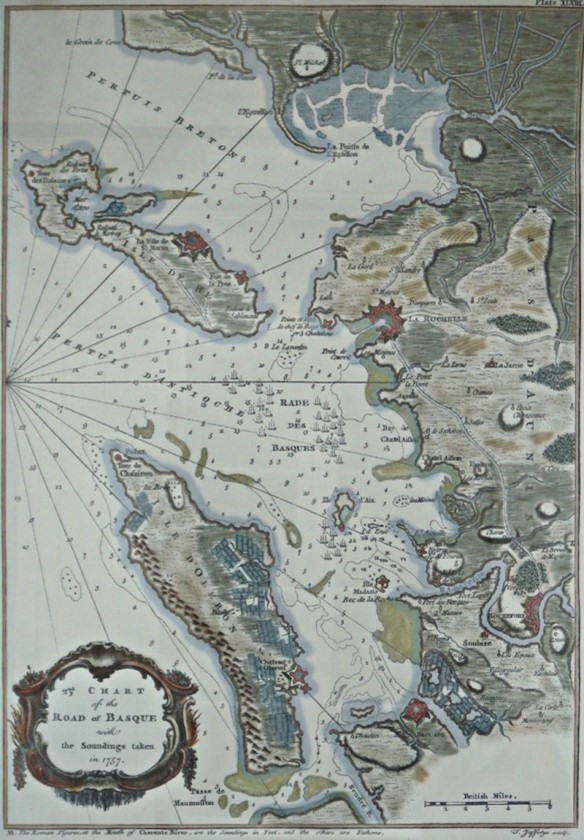

Those officials included Lord Castlereagh, minister for foreign affairs, and John Wilson Croker, secretary of the Admiralty, two key individuals from two key institutions. They met with the newly appointed royal government on 12 July in order to address the pressing matter of what was to be done with the fugitive Napoleon. At that time, a few days before Napoleon actually surrendered, the British and royalist officials knew that Napoleon was on the Ile d’Aix off Rochefort and there were two frigates at his disposal, ships which had been provided by the provisional government so that he could leave for America. However, the British blockade had prevented them from leaving and Napoleon was therefore stuck, despite many ingenious plans and schemes to smuggle him out and away. Still, the British and the royalist government in Paris, a government which did not yet hold sway over western France, thought it unlikely Napoleon would give in quite so easily and so concocted a plan to seize him. Of course, ultimately, it was not carried through. Even so the plan itself gives a wonderful insight into the ruthless determination of men like Castelreagh and Croker as they sought to put an end to the Napoleonic Wars by putting an end to Napoleon. The plan is set out in great detail by Croker in a letter he writes to Admiral Hotham on 13 July 1815 and which was to be delivered to him by a French frigate captain, Henri Gauthier de Rigny. The message calls on the British to attack the Ile d’Aix and to seize Napoleon or to sink the vessel he was on if that proved impossible.

“Lord Viscount Castlereagh, His Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, has requested me to communicate to you some circumstances relative to Napoleon Buonaparte, and to suggest to you the course which the British government would wish you to pursue under the new aspects which affairs have assumed. I have therefore (though I have here no public character) undertaken to make this communication and I have assured His Lordship that you will, under the pressing nature of the case, overlook the want of official form, and conform your conduct to His Lordship’s wishes which would be those of my Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty if there was time to consult them.

The French government has received information that Buonaparte has embarked at Rochefort onboard one of a small squadron which the provisional government had placed at his disposal and it is understood that this squadron is anchored under the forts of the Ile d’Aix ready to escape by the first opportunity.

I understand also from the French Minister of Marine that the British squadron in that neighbourhood consists of two or three ships of the line and two or three frigates and in some communication I have had with Lord Keith on this subject before I left England, his Lordship assured me that his attention had been directed to Rochefort, [so] I cannot doubt that except under some very extraordinary circumstance, the escape of Buonaparte’s squadron, or any vessel of it, from the Charente is impossible; but, as it is, for obvious reasons, of very great importance that the question with regard to this person should be brought to a decision as speedily as possible, Lord Castlereagh wishes you to consult confidentially with the officer of His Most Christian Majesty who is the bearer of this letter, and to afford him the most cordial assistance in all practicable measures which he may be disposed to recommend for the capture of Buonaparte.

The plan which has struck His Lordship and the French minister as being the most likely to succeed, and which will be suggested to the French officer, is as follows:

If it shall ascertained that Buonaparte is onboard one of the ships in Aix Roads (I say if, because, notwithstanding the information of the French government on this point, I cannot but doubt that he has embarked with any hope of escape from this particular port which of all others is the most susceptible of blockade and I consider it most probable that he has either not embarked but has spread the noise of his having done so as a blind, or he intends to land again and endeavour to escape by some other means which he hopes may be concealed by his pretense); I therefore repeat if it be ascertained that Buonaparte is certainly embarked in Aix Roads it may be concluded that he is, as he thinks, sure of the governor and garrison of the forts which protect the anchorage and as those forts are very considerable, I entertain little hope that you could think yourself justified in attempting to reduce them or capture Buonaparte while lying under their full and active protection.

But, under the present circumstances of France, it seems reasonably to be doubted whether the governor of Aix, if properly summoned by the king’s authority, would attempt to fire on the ships of His Majesty’s allies in the execution of His Majesty’s orders. It is therefore considered expedient that before you proceed to attack the ships, you should send a flag of truce to the governor of the Ile d’Aix to say that ‘by the King of France’s express command you are about to seize the person of the common enemy, that you have no hostile intentions against the ships or subjects of the Most Christian King but, on the contrary, look upon them as allies as long as they do not oppose the king’s authority. That you do not mean to capture or injure the French ships or to interfere with them beyond the mere seizure of Buonaparte’s person, except so far as their own opposition may render it necessary and as to the governor himself, that if, after this notice, he takes part with Buonaparte or permits a shot to be fired at you, you will pursue the most energetic measures in your power and will hold him responsible in his own person for any mischief that may be done. And you may add that the French government has apprised you that the king will consider the death of any British sailor employed in execution of his commands as a murder of which the governor of the garrison from which the shot may proceed will be held guilty.’ This notice on your part will be accompanied by an order from the king to the same effect and as soon after they shall have been delivered to the governor as may be possible, it seems expedient that you should commence the attack as it would be preferable not to give the influence of Buonaparte’s renown time to operate on that officer’s mind.

Your professional skill will be your guide as to how far, in the uncertainty in which you will be as to the conduct of the governor, you will think it justifiable to pursue your attack. Lord Castlereagh feels that it is of the most urgent importance to seize Buonaparte; but he also feels that the safety of His Majesty’s ships ought not be compromised beyond the ordinary risks of a naval engagement and he is sincerely desirous of avoiding the effusion of blood which, however, he is inclined to think maybe best effected by bold and decisive measures; and if the ship in which Buonaparte may be should, by an obstinate resistance, drive you to extremities, he feels that you ought not for the sake of saving her, or anyone onboard her, to take any line of conduct which should increase in any degree your own risk: the consequence of the resistance will be chargeable on those who may make it. If, however, you should find it impracticable with any fair prospect of success to attack the ships or, if having attacked them, you should not find it expedient to continue the engagement, you shall of course continue your blockade with the usual vigour and if you should require any increase of force you may either draw something from the neighbourhood of Brest or write to Lord Keith by one of your cruisers and send a duplicate of your letter to the Admiralty by way of Paris. I shall remain here until the 24th or 25th instant and after that time if you should have communication to make to the Board which seems to require despatch, you may put them under cover to the English Minister at the Court or send them by an express.

If Buonaparte, for himself, or the governor of the forts or commander of the squadron for him, should propose to surrender on terms, Lord Castlereagh is of opinion that you should reply, as the fact really is, that you are not authorised to enter into any engagement of that nature; that your orders are to seize the person of Napoleon and his family and to hold them for the disposal of the allied powers unconditionally. It is unnecessary to say anything as to the safe custody of Buonaparte if you should be so fortunate as to take him, as your orders on that head are sufficiently ample but that particular of your present orders which enjoins you to convey Buonaparte without any delay to a British port in the event of his capture, Lord Castlereagh thinks should not be literally followed under the circumstances in which you would obtain possession of him and his lordship wishes therefore that you should delay sending him to England until you have had communication with him on the subject.

Whatever course you may on other points pursue, it must be recollected that your forces are to be considered as acting in concert with those of the King of France, within the waters of his kingdom; and it is therefore expedient that as little hostility (as may be consistent with the success of your great object) should be employed and if the forts and ships should either by force or summons be induced to acknowledge the king’s authority, you will naturally feel that (with the exception of possessing yourself of the Buonapartes) the British government would not wish you in any way to interfere with them.

This letter, the substance of which was settled last night at a conference with the French ministers, and has been communicated in extensio to the Comte de Jaucourt, the Minister of the Marine, Lord Castlereagh and I trust you will consider as a sufficient authority for you to pursue the course therein suggested. I shall this day forward a copy of it to Lord Melville and I have no doubt that his lordship and the Board will fully approve and sanction all the Secretary of State’s propositions. I request to have the pleasure of hearing from you with the least possible delay and have the honour to be etc.”

And there it was, stated in black and white: “if the ship in which Buonaparte may be should, by an obstinate resistance, drive you to extremities, he feels that you ought not for the sake of saving her, or anyone onboard her, to take any line of conduct which should increase in any degree your own risk”.

The admiralty was ordering Admiral Hotham to sink the ship which carried Napoleon. It would have been a very difficult order to carry out but, fortunately for Hotham, he only received it after Napoleon had surrendered. It now sits, along with much more correspondence, amongst the Hotham Papers in Hull.