An odd eyewitness account

This is a series of letters by Mrs Thompson, wife of Thomas Thompson, Dean of Killala, to her aunt. They were written in October 1798 and describe in detail Mrs Thompson’s tribulations, for she was amongst those who had become trapped when General Humbert landed in August 1798. Her confinement had not been too unpleasant, for she formed part of the group caught in Bishop Stock’s castle.

“Tom [her son, Thomas] wished to give a take-leave entertainment to all our neighbours and on the 22nd had a number of them to dine with us – three ships had been seen early in the morning but as they hoisted Inglish colours no danger was apprehended. I looked at them from an eminence through a glass and thought them a beautiful sight with all their white sails up, the day was remarkably fine; two of the bishop’s sons and another gentleman went out in the king’s boat to take a nearer view of the vessels. They were to have been part of our company and we waited dinner for them til near six o’clock but on their not returning at that hour it was generally agreed that they had been kept to dine aboard by the English officers, particularly as some fishermen asserted they had sold fish to the vessels and they certainly were Inglish, [so] we went to dinner without having the remotest idea of fear of any kind but enjoying the thoughts of all the news we should have on the return of our gentlemen.

Just as the ladies and I retired to the drawing room we heard a bustle in the street. I ran to the window to see what it was, everybody was running to and fro in the greatest confusion, so much so that no person heard my repeated calls to know what was the matter; upon which I ran into the street myself and then learned that the French were actually marching along the shore into the town. I flew into the parlour and told the gentlemen who, unconscious of the danger, were cheerfully taking their bottle; you may suppose everything was upset. The captain of the yeomanry etc, etc, a Captain Tills [sic], who commanded a party of the Prince of Wales Fencibles that had quartered there but two days were part of our company. Tom sent out for his horses and desired me to prepare to be off instantly. I collected my children, flew with them through a private way which the bishop had made for our accommodation through the gardens of both houses to the castle; happily for me that was the way I went, for had I went the street way I must have been shot as the French were in the town. My strength failed me and I fell almost lifeless with my youngest child in my arms, the other three clinging to me rending the air with their cries. Fortunately, one of the bishop’s sons came that way to see what was become of us, and assisted me, but soon as I got into the friendly and hospitable mansion of his father my senses forsook me and for several hours I knew not what happened.”

“When returning reason resumed her seat I felt and saw the horror of our situation. The French were in full possession of the castle, we prisoners with all the family and a number of others in the supper storey and nothing to be heard but the din of arms. However I found consolation in finding my husband and children about me, he, poor fellow, was only anxious for me in the midst of the tumult. However, I got better and through the assistance of that invaluable family was enabled to bear my situation with some degree of composure. We sat up the whole night, indeed it was impossible to do otherwise for there was scarcely room to sit much less to lie down in the four rooms on that floor; all the rest of the house was occupied by the invaders who found it neat and elegant for their reception. Two beds in each bedchamber preparatory to the bishop’s visitation which was to have been held the following day, and as it was his first, everything was laid out in the handsomest manner, the drawingroom was furnished with beautiful cotton which the wretches afterwards made shoe rubbers and saddlecloths of.

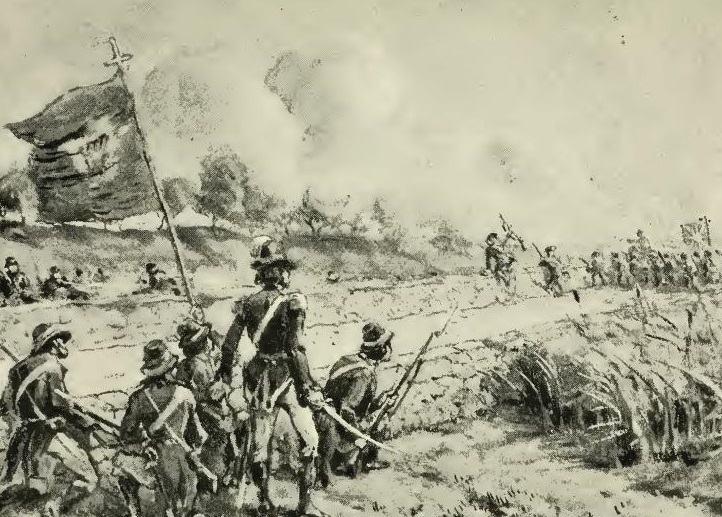

I learned that the yeomanry, 40 in number, and the Prince of Wales, only 20, headed by their officers had turned out against the enemy, weak force indeed, and soon repulsed. Two yeomen were killed on the spot, more fled but the greatest number of the fencibles and their officers were taken prisoners and marched to the gates of the castle where the French general demanded admittance. Some of the clergy that were there had fled, among the rest our friend Seymour, those that remained joined by a few other gentlemen from the town and the bishops domestics were mad enough to intend opposition and armed themselves for that purpose, but his lordship and the dean remonstrated against the folly of such an attempt and our enemies were soon in possession after seizing all the horses they met on their way, among the rest five of ours. The two men servants that had been sent out for them never returned, they wisely made the best of their way to Castlebar which we did not know until we came home. Immediately on entering the castle the general called for the bishop and addressed him in a very polite manner with an offer of a handsome establishment under the new government, for that they had not a doubt of effecting a revolution in a few days, that there were 25,000 French then landing in Donegal and different parts of the kingdom and that they looked upon themselves as masters of Ireland where they came for the purpose of restoring liberty and peace and making an oppressed people happy.

The bishop civilly rejected the offer coolly replying that he had taken too many oaths to the present government to find the breaking of them so easy to his conscience, and that he felt himself bound by the most sacred ties to his king and country. The general called him a man of honour, told him he intended making that house his headquarters and requested that everything might be ordered accordingly. Supper and wine were instantly laid and every domestic in the house employed in striving to supply their innumerable wants. Beds in every apartment were already prepared and the entire house (except the upper floor), offices and yard were instantly occupied by our invaders. They ordered light in every window during the whole night and desired every person to give up their arms on pain of instant death in case there should be any found upon them; the same mandate was issued in the town where every house was occupied by our new acquaintances, our house was full and those that took possession felt themselves perfectly at home for while the provisions, wine and liquors lasted they ordered it just as they pleased. We had two faithful servants who never left the house but endeavoured to preserve our clothes, little plate, etc, which by degrees they stole down to the castle to us, otherways my poor children and I should have been naked.

Poor Captain Tills and his men were put aboard the French vessel and in three days after sailed for France. They also sent 14 or 15 of the best horses; they took some of those beautiful hunters belonging to the bishop’s sons. For three days after they landed we saw nothing but repeated bodies of the French, their arms and baggage coming from the ships which had anchored about two miles from the town. A requisition of everything they wanted was made to the bishop and the general’s conduct became extremely outrageous whenever his orders could not be obeyed. At one time he demanded 50 boats to bring up their ammunition etc from the ships; on their not being procured he marched our bishop off with the intention to send him prisoner to France; however, when he found the worthy man was not to be frightened by his treats to do what was impossible, he marched him back again. Judge of our situation at these periods, for indeed it is not to be described; they planted their standard in the courtyard and put up the most inflammatory proclamations which soon drew forth the deluded wretches by hundreds and thousands who at all hours day and night marched in triumphantly. What a scene we from the windows of our prison beheld: the arming and clothing of 5,500 of these ruffians, scarcely a man of inferior rank in or about Killala that did not join them, and some of the respectability in the neighbourhood, Captain O’Dowd that was hanged at Ballinamuck had 500 per year in that county, was a yeoman in that corps and voluntarily took the oath of allegiance to the bishop a day or two before the French landed. The titular bishop’s brother was an active general, he was hanged at Killala.

The day after they landed they took Ballina, a pretty town about six miles from Killala. There was an opposition but it did not avail. Mr Fortescue (a clergyman) was mortally wounded and one or two yeomen badly wounded but have recovered. They made Colonel King’s house at Ballina headquarters and were soon joined there by croppies innumerable, some of them returned flushed with success to Killala and began to prepare busily for their further progress. On Tuesday the 26th they marched for Castlebar and on the morning following, to the astonishment of the whole kingdom, since they had possession of that town not withstanding the strong force of our army three to one as I have been informed; the French general said he had not seen so obstinate a one even at La Vendee. In five minutes what a glorious victory should we have gained but for the retreat of our army, for the French were absolutely going to surrender at the instant the unfortunate race began and left them masters of the field and all our cannon.

Never shall I forget the revelling and joy that took place at Killala on the arrival of this news; the insolence of victory was scarce to be borne in the insurgents who flocked in tenfold. What a night of horror to u who did not know but that all we held dear in that town had fallen in the action. Doctor Ellison and my brother-in-law prisoners with us; you may suppose what their feelings were, not knowing how their familys or propertys were disposed of, for all communication was cut off from the loyalists, we did not know what passed in any part of the world accept the miserable spot we were confined in. The accounts brought in by the French rebels we could not depend on. My brother and Doctor Ellison solicited leave to go home as they would be equally their prisoners in one place as an other; it was granted them and they were taken to Castlebar by two different parties on two different days. Mr Ellison contrived to let us know of his safe arrival and that all our friends were living, a great relief, that.

We heard that Castlebar had been retaken and that peace and quiet were re-established there, however our apprehensions for its safety were soon awakened again by witnessing the vigorous preparations for the rebels for an attack on that town. We reckoned 700 pikemen marched from their camp in the bishop’s demesne besides those bodies armed with firearms, they were joined by numbers beyond calculation all along the road until they reached the environs of the town where happily the yeomen and loyal inhabitants of Castlebar repulsed and beat them back; it was a glorious defeat for there were not more than 50 military in the town to repulse them if they had made good their entrance.”

“The French before this period had left Castlebar and those at Killala were gone also to join the main body, except one officer who was to remain with 200 Irish recruits to protect the town; you may judge how we liked such protectors as the united men. As the officer commandant stayed behind solely for the purpose of defending us and thereby ran the risk of losing his own liberty, he thought it but reasonable that one of the bishop’s sons should go with the French troops to Castlebar as a hostage for his person in case of the English becoming again masters of Killala. To this there could be no objection made and his third son ( a fine lad) was sent off with the army. However, they did not take him on to Ballinamuck, he remained at my brother-in-law’s house until he came down with the English to take Killala. During all that time we did not know but that he had remained with the French and perhaps had fallen in the action. Two more French officers had fled to us from Newport and they and the commandant became one family with us prisoners; we got down to the drawing room on the second floor and began to breathe the fresh air by walking in the garden. Our captivity became less irksome and we would have waited with some degree of patience for the issue of the business had it not been for the insolence and threats of the rebels who daily appeared in greater numbers than before. They became vociferous for arms of which there were none left to give them, they then demanded a requisition of all the iron in the county to make pikes, cut down the bishop’s trees for handles and set all the smiths and carpenters in the place to work. Hundreds of those formidable weapons were made before our eyes in his lordship’s yard where his forge and workshop were, his own smith and carpenter forced to work. The commandant proposed arming the few Protestants in the town to enable them to protect their properties against the midnight depredations of this rebellious crew, but it was violently opposed by them [so] that they poor Protestants got intimidated and declined the commandant’s proposition declaring that they would trust themselves to the protection of the patrole.

What a night of alarm but it passed off pretty well. The wonderful resolution, coolness and courage of those three French officers still kept the rabble in awe, the commandant particularly was a man of temper and discretion and on him all our hopes of safety rested. He sat up many nights to watch us and to enable any who would attempt it to take a little rest. We certainly owe our lives to him and the other two officers; latterly they wished for the arrival of the English army as much as we did, for the rebels began to murmur at their favouring the Protestants and threatened to be no longer governed by them. In short, our situation was truly pitiable, the plunder and devastations committing around us was shocking, not a day that the people of the country were not flocking in to the castle to request the bishop would represent their tale of woe to the commandant; he did all that was possible for them by issuing proclamations against it and threatened death to the offenders. But it was in vain.

Were I to enumerate instances of this sort it would swell my narrative to a most enormous packet. We had heard that the French army had marched towards Sligo and that they were pursued by an army of 21,000 English commanded by Lord Cornwallis in person. We felt it a critical moment of danger to us. Between the withdrawing of one government from us and the approach of another the Roman Catholics effected to be mad with apprehension that the Protestants would murder them and wished to put it out of their power by being guilty of the act first. But miraculously was their fury at all times restrained, however we were in a sad fright. The newspapers, both English and Irish, have so fully stated the battle of Colooney and our decisive victory at Ballinamuck that I need say nothing on that subject. Flying reports reached us of both from straggling rebels who had fled from each place. The commandant in confidence to the bishop acquainted him with the truth of it, and it was mutually agreed between them that a profound silence on the subject should be preserved lest the rebels becoming desperate at the defeat of their allies and the slaughter of their brethren should retaliate by murdering us who were in their possession. Their principal leader had before made the castle his headquarters and occupied the best bedchamber in the house, it was on the same floor as the drawing room, where we then messed, so that we became subject to all the interruption of him and his colleagues whenever they pleased. All was liberty and equality.

We by this time got a very agreeable addition to our gentlemen. Mr [William] Fortescue, member for the county Louth. He had come from Ballina to enquire for his brother (the clergyman who I mentioned in the former part of my letter was mortally wounded), he did not know of his death having known the defeat of the French he expected to find the poor prisoners all at liberty. Judge the surprise of this Mr Fortescue when he was taken prisoner himself and sent by the officer of Ballina under a guard to our commandant to be examined as a spy. However, he easily proved the pious errand that brought him and related the defeat of the French which he corroborated of the persons of the French officers which he had met prisoners going to Dublin. We all felt interested for one in distress as he appeared much grieved for his brother the bishop asked the commandant to allow him to remain prisoner at Killala instead of Ballina to which he consented and Mr Fortescue became an acquisition. Particularly so to the bishop as he spoke French fluently, which in a great measure relieved his lordship who was worried to death as an interpreter. This gentleman was a fortnight in captivity and when he came to the castle he did not think it in the nature of things but that we should see an English force before 24 hours come to our relief. But alas we were left there, though not forgetting by the world forgotten, we often discerned vessels in the offing with aching hearts for our enemies would always have French or Spanish sometimes we would indulge the delusive hope that they were English coming to our relief.

Often have we been terrified to death with the idea of the town being bombarded from some of those ships which constantly appeared for reports of the kind were daily propagated, I am sure for the purpose of frightening us, as there was a great quantity of gunpowder belonging to the French stored in the offices of the castle. Latterly it was buried in a great hole in the garden and hid under arched corn stands to preserve it from the rebels.

The French officers certainly did everything possible for our safety and to those three brave fellows we owe the preservation of our lives. There was one at Ballina and though the newspapers give him equal merit wit the other three yet he was a very different character. Personally we knew nothing about him, but Charost [Amable Charost], Buda [Philippe Boudet] and Ponsoe [François Ponson] were indeed gentlemen and men of honour. They amply supplied us with provisions for every atom the worthy bishop had was completely eaten up the first five days, everything within doors, wine and liquors, all his fat sheep and cattle, his hay old and new, his years turf and every potato he had in ground, his old oats and all his corn and ground destroyed by the cattle driven into his demesne to be slaughtered by the rebels. In short, he had nothing but his milk cows which were protected by the French officers in pity for our poor children whose chief food was potatoes and milk for flour could not get to buy and what the French supplied us with was scarce and very bad. But these devastations were not so bad to the bishop for every person who had anything to lose lost it. The rebels were not to be refused, our protectors were losing their authority and the pikemen who for the last fortnight assembled in thousands threatened destruction to them as well as us.”

“Latterly every day new modes of death for the Protestants were proposed: burning us in the cathedral, firing at us through the windows and starving us to death were the plans severally started but the blood-thirsty wretches not agreeing still deferred the execution of their diabolical plot. They argued as a plea for their sanguinary intentions that the rebel prisoners at Castlebar were treated with great cruelty and why should they longer defer retaliating on us who were in their power. An awful crisis you must allow. It was debated that an ambassador should be sent from each party to enquire into the truth; the bishop thought it a good expedient as we should at least gain 48 hours reprieve by it and in the intermediate time the army might come to our relief. Think my aunt upon the situation of your poor unfortunate niece when her beloved husband was the person pitched on by the rebels to go on this errand. No other person would they agree to; my soul died within me on their issuing this mandate and life had very nighly taken flight when the almighty inspired me with courage and resolution and instead of restraining I urged the immediate departure of all my soul held dear. He set off attended by a rebel chief who was not to lose sight of him for a minute until they returned. … The ambassadors returned the following evening; the joy that took place on the arrival of the dean made us all forget our past misery and everybody clung about him as their guardian angel. He brought back an answer from te general that pleased the rebels and his companion seemed very well pleased with his embassy. We slept in some degrees of peace that night after hearing him relate his adventures. He had met multitudes of rebels all along the road chiefly pikemen. He was suffered to pass unmolested as his errand was made known to them all. On arrival at Castlebar joy was visible on every countenance and the eagerness of the people to hear all about the Killala prisoners made them almost tear him off his horse. However, he got up to the general’s quarters accompanied by his companion, Captain McGuire, where he delivered his dispatches and then went to receive the caresses of his family. You may judge what a meeting it was; the joy of the moment was soon lost in a torrent of anguish at the uncertainty of what might be our fate on his return.

Immediately on his entrance into Castlebar the rage of the multitude was such that they wanted to hang Captain McGuire immediately. But the dean declared they should hang him first for that his honour was at stake for his safe return and independent of that our lives at Killala must inevitably be the forfeit if anything happened to the captain. I believe the poor devil was a good deal frightened, however he was treated with great kindness and attention at my brother-in-law’s; Tom and he slept in one room with a guard upon them of two officers. The captain’s cares were soon lost in a sound sleep and my poor Tom then found means to make known the misery of our situation and to implore the general to hasten a force to relieve us or we must inevitably fall a sacrifice. He left him in full possession of our situation and of the situation of the place etc. And to Major Taylor we are much indebted for strongly urging the general to name an earlier day for the attack on Killala than he intended; this was on Wednesday night and sooner than Sunday it could not be effected as they must cooperate with te Sligo army to whom expresses were sent. Friday passed on pretty well, multitudes of pikemen assembled in the camp to our great terror but the French officers watched them closely and by manoeuvring and sending them here and there in different parties, diverted their minds from what we had ever reason to fear they were planning.

On Saturday after breakfast we were thrown into a shocking fright by clearly seeing houses on fire along the Sligo road, though we were all convinced by glasses that it was the case yet the gentlemen tried to make our enemies suppose it was kelp that was burning along the shore. Perhaps this fiction might have quieted their minds for a little had not a priest arrived with intelligence that it was certainly the case and that he was an eyewitness to the houses being on fire. The rage of the rebels was beyond anything you can conceive. Instant destruction was threatened to us and we every minute expected to see Killala in flames. What but the hand of the Almighty could have restrained them. Te greatest confusion took place and the horror of the moment was such that I scarcely remember the incidents that occurred. The French officers tried to console us and declared they would lose the last drop of their blood in defending us from massacre. They privately gave our gentlemen arms and ammunition and exerted themselves in every manner possible to establish a little peace and order among the people. Some vague reports came in that some English force was appearing about 12 miles from the town. The commandant encouraged the Irish generals to take forward their forces to repel the enemy; they were very anxious for a French officer to head them but for them to remain with the Irish forces at Killala to prevent the English from entering the town. By this means we got rid of the main body of the enemy, only about 400 remaining in the town and its environs.

What a night of hope and fear. None of us went to bed, few lay down. It was the most dreadful night of rain and storm I ever remembered and in fact made us despair that our troops could march. Next morning a friend out of the town sent us word not to attempt assembling at prayers as usual, for that he had overheard it declared that we were all to be seized upon at that time and carried to the church for execution and also for none of the family to appear outside the doors or they would be shot like dogs. What a distracted state we were in, hunger, not to be restrained, assembled us at breakfast where we were interrupted by the French officer from Ballina. A great ruffian, a Major Keen, an Irishman who had come over with them, bursting into the room in great disorder accompanied by two or three ruffianly looking rebel captains. We soon learned that the English were in possession of Ballina and that these heroes had fled to join their friends and prevent their taking Killala. The French officer had the impudence to produce a pair of epaulettes which he asserted he had torn off the shoulders of an English officer and that he had wrested the colours out of the hands of another and planted them at the door of a rebel chief in the town. These were the old volunteer colours and old epaulets which he got in Colonel King’s house where he lived, as we afterwards learned.

What a terrible state of suspense, anxiety, dread and fear were we all now in. After these gentlemen had breakfasted we retired and mentally offered up our prayers to God for a happy issue to this day’s business. Our French officers rallied the Irish troops and headed them to meet our army. We all lamented the necessity of three brave fellows being obliged to risk their lives and heartily prayed they might return to us unhurt where every protection was ensured them by the bishop. We saw from every window in the castle the greatest confusion going forward, hundreds of miserable women, children and old men coming in at every avenue of the town, just as if they apprehended no danger there. Oh my God what a state we were in, worse than a thousand deaths. Our gentlemen had all their private arms in readiness, so disposed that they could instantly lay hold of them in case of a rush into the house, which was to be apprehended from the rebel guards. However, on the fire commencing, they all fled, the gentlemen and servants shut the gates and doors, we heard the firing for some time before we discerned a red coat and began to dread it might be some deep laid plot against us when somebody amongst us cried out ‘I see the red coats, I see the rec coats’. I cannot describe it, nor can I think of it without being blinded with my tears. The gentlemen insisted we women and children should stretch themselves on the floor in one of the rooms. It was difficult to get us to comply, we were absolutely frantic, sometimes falling on our knees but unable to pray, at other times clinging round each other’s necks but unable to speak. All this time the most tremendous fire going on in our hearing.

At length we were so terrified that we were glad to do as we desired and stretched flat upon the ground, each poor mother collecting her frightened children around her while the men were peeping from one part or other of the house at the slaughter going forward. Poor Mr Fortescue, who I mentioned in a former part of this letter, received a ball in his forehead; 14 had come in at the window where he stood. Not five minutes before he had made Mrs Stock and I quit the very spot. Thank God it did not enter the skull, he was able to travel to Dublin in a few days and is getting on very well though the bone is a little injured, but his life is in no danger. The French officers surrendered and made off to the castle; just as our good commandant was rapping at the door he was fired at; the ball got under the arm that was raised at the knocker and went through the hall door at the instant it was opened for him. A great escape and one we all rejoiced at. Shortly after the house was filled with our deliverers and the English colours flying at the very door of the apartment the rebel general had quit a little before. We women were called on to thank our brave deliverers which we did by embracing almost every officer we met. What joy was manifested in the countenances of them all; had we been their mothers, wives or sisters they could not have shown more.

Lord Portalington with whom I conversed and who commanded the Sligo army, declared it had been a most painful march for him and his officers for he heard it confidently asserted that the bishop and the dean were to be hanged and he feared that the army might not be in time to prevent it. Even the men on their entrance into the gate cried out are the bishop and the dean safe and on being answered in the affirmative exclaimed ‘thank God, thank God’. You may suppose what a bustle took place when there were above 2,000 men with ammunition, baggage, etc, as many officers who could be accommodated at the bishop’s were. The general, of course, and his suite. We women had gone through too much during the day to be able to appear at dinner. At the close of the evening our alarm began anew; the violence of the soldiery could not be restrained and they set some houses on fire which happened to be exactly opposite the gunpowder that was logged in the haggard. Fortunately the wind blew from it, otherwise we should have been in extreme danger. As it was we were all dreadfully frightened and did not rest in peace all that night. Next day our spirits revived and we enjoyed a very pleasant society among the officers who were in crowds at breakfast, dinner and supper while they remained at Killala. The daylight exhibited more clearly the slaughter that had taken place, the unfortunate wretches that had fallen were in numbers to be seen lying in the street. Opposite the gate we from the windows saw many dead carcasses, every potato and corn field about the town bore witness of their defeat. For days they were collecting them and the unfortunate female relatives trying to inter them in great holes dug for the purpose. Many of our late companions were recognized, among the rest the leading general who fell early in the action. Many worse characters escaped and have not since been heard of. The court martials commenced but went on so slowly that I despaired of getting home if I waited for the general to move. From day to day we were induced to stay an entire week after our captivity ended; with two carriages, which we had sent for to Castlebar, waiting for us, at length we requested a guard and were escorted by 60 horse. With eyes overflowing with tears and hearts with gratitude we quit a house where we had experienced every mark of friendship, tenderness and love from its worthy owners.

On Saturday the 29 September we entered Castlebar our carriages in the centre of sixty horse never can I forget my feelings on that occasion—I thought I should have died with excess of sensibility at seeing the general joy that indeed every description of people expressed there at the doors & windows lifting up their hands & Eyes in token of thankfulness for our deliverance—while the men threw up their hats & rent the air with their huzzas—but what affected me most was the poor falling on their knees in the dirt—I thought I never should reach our own door, when I did the scene that followed was more than I am equal to describe—I found myself surrounded by all those dear Friends who had suffered so much for me & we mentally returned thanks to our Almighty deliverer—for days the house was crowded with congratulatory visitants and we felt happiness inexpressible.

What became of our French friends, you have seen in the newspapers—they were treated with marked attention by us all—for the day or two they remained at Killala after the Battle—on their departure they gave us all the fraternal embrace & seemed thankful for the civilities they had received—they continued for near a fortnight in Castlebar—and immediately on our arrival came to visit us—we had them to dinner and on their leaving town we again got the fraternal embrace. On their going to Dublin they were complimented by every friend of the bishop’s and the primate, who is brother in law to the bishop, waited upon the Lord Lieutenant and represented their conduct to us while we were in their possession. They were received by his Excellency accordingly; last week they sailed for England and are to remain at Litchfield until they are exchanged. Thus ends my history and I hope my dear aunt will allow that I deserve her thanks for writing such a long letter. I know what a gratification it must be to my friends at Loughrea and in that idea I am amply repaid. Ever your affectionate niece, B Thompson.”