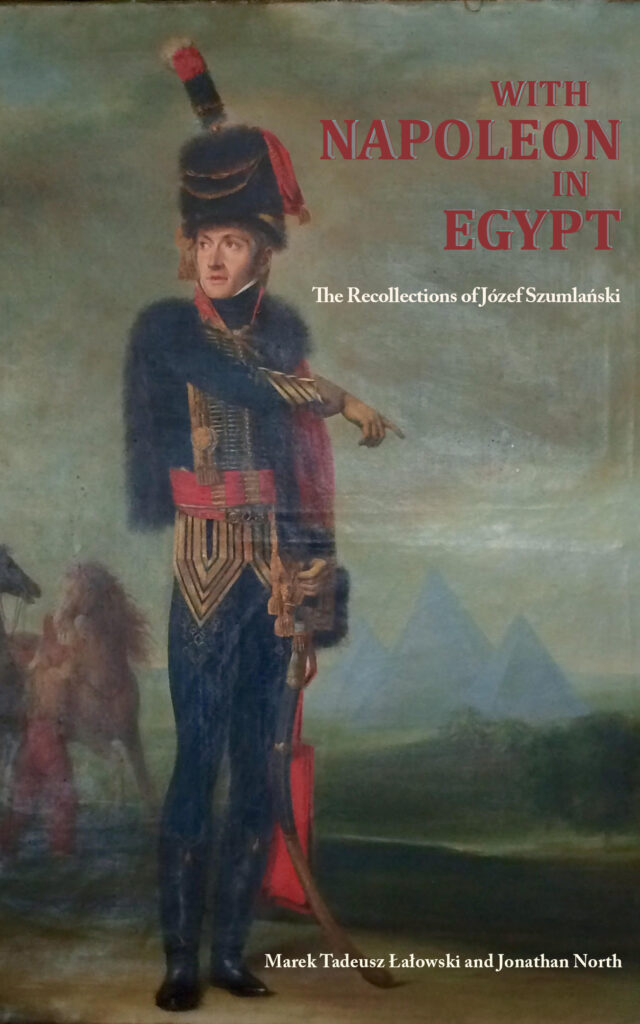

A short memoir by a Polish cavalryman who took part in Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798. It sets out (briefly) his own adventures, and adds some observations on Egypt, its people and its culture. Our Polish hussar took part in the capture of Malta, the landing near Alexandria and the battle of the Pyramids.

After witnessing the fall of Cairo he fell ill and was being evacuated back to France when he was captured off a Greek island and held by the Turks. Only when a ransom was paid for him was he freed from Constantinople so he could return to Europe.

The book is currently available in Kindle here and here

Incidentally, our hussar, who went on to serve Prince Poniatowski, left an interesting account of that prince’s life and achievements.

Stanisław Kostka Bogusławski produced the first serious biography of Poland’s most famous Napoleonic hero, in the preface to the first Prince Józef Poniatowski in 1831. Entitled The Life of Prince Józef Poniatowski: Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Army and Marshal of France [Życie Xiążęcia Józefa Poniatowskiego, naczelnego wodza woysk polskich, marszałka państwa francuzkiego] it sought to present a full if, in our eyes, rather hagiographic, account of the soldier’s life and achievements. As part of his research Bogusławski trawled through official documents and correspondence but also sought out those who had been close to Poniatowski or sent questions to those who had known him. Among those contacted were Poniatowski’s loyal adjutants, Ludwik Kicki (1791-1831) and our old friend, Józef Szumlański. The questions and answers can now be found in the archive of Józef Szumlański, now stored in the Scientific Library of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Kraków. With thanks to Marek Tadeusz Łałowski for translating this interview by correspondence.

AN INTERVIEW BETWEEN S. K. BOGUSŁAWSKI AND COLONEL J. SZUMLAŃSKI

1. Your Lordship, do you know whether, in addition to the reports and official dispatches, there exists an account of the glorious campaign of 1809 by Prince Józef Poniatowski himself, something along the lines of his own description of the campaign of 1792?

I can certainly guarantee that Prince Józef Poniatowski’s description of the battles fought in 1809 was not written by him. The history of this glorious, and rather famous, campaign for the Polish troops was to be compiled from the writings, reports and daily orders found in the Chancellery of his General Staff. Some of those officers active then are now dead, but some I know to be still alive. Among the latter, I recently had the pleasure of seeing [Franciszek] Młokosiewicz, a brave lieutenant-colonel in the Vistula Legion, seriously wounded at the time. I know that General [Józef] Rautenstrauch, the chief of staff, or rather the prince’s personal secretary, dealt with this subject, and even read to the Countess de Vauban, and in my presence, following my return from Paris to Warsaw, the introduction to this history, something written in French. I have infinite regret that, to date, nothing like this has been published in print.

I, then being by the prince’s side as first adjutant and attached to Duke [Syerghey] Golitsyn, commander of the allied [Russian] army, and given the duty of maintaining military relations between the two armies, actually possess some rather interesting documents concerning these famous events. Among them there is a letter from the Duke de Ponte-Corvo, the present King of Sweden [Jean Baptiste Bernadotte], written to Prince Poniatowski on the occasion of his victories and Napoleon’s letter to Emperor Alexander after the battle of Wagram. Both these letters are very interesting. If you request these, I shall not fail to send you copies.

2. What character did the prince show when in conversations with those around him? How competent a military commander was he?

Prince Poniatowski was a different man in private from that he showed in public. In private life his character was mild, courteous, and unspeakably charming, and his conversation was the model of the most polite tone and the noblest manner of thinking. In his public behaviour, however, all the traits of his character were those of a great man, and his voice, when raised in the service of the Motherland reached the highest degree of fervour and eloquence.

[Note: regarding the question on military competency, although Szumlański’s did not give a direct answer the resulting biography by S.K. Bogusławski spoke highly of the prince’s abilities and his war record: against Russia in 1792 (Zielence), Austria in 1809 (Raszyn, the offensive and capture of Western Galicia with Lublin, Zamość and Lvov, the recapture of Kraków}, against Russia in 1812 (Smolensk, Borodino, Tchirikovo and Vinkovo) and against the Allies in 1813 (Lobau, Zedlitz, Leipzig).

3. Did he rely on, or place blind faith, in anybody’s opinion?

In insignificant circumstances he used to rely on the opinion of those who knew how to win his appreciation and respect. Such men as: generals [Michał] Sokolnicki, [Stanisław] Fiszer, [Jean Baptiste] Pelletier, [Franciszek] Paszkowski and [Jean Baptiste] Mallet [de Grandville]. In important and decisive matters, he did not consult or listen to anyone, but followed the path of his own genius, and it was then that the talent of a great leader was fully revealed.

The Convention of Warsaw, following the terribly bloody battle of Raszyn [9 April, 1809], and concluded with Archduke Ferdinand, was an agreement he insisted upon and held true to despite the greatest difficulties and opposing views, and which, in that fateful campaign, ensured the success of the Polish army. The same can be said for other victories in 1809, 1812 and 1813, which convince us of this undeniable firmness, whatever the wicked and jealous detractors of his immortal fame choose to say.

4. Was he fair with subordinates when rewarding for bravery or in terms of promotion?

Being himself the model of incomparable bravery, he knew how to value it in others too. Therefore, he rewarded without distinction or rank all those who were lucky enough to distinguish themselves before his eyes. Since such fortunate ones were small in number, therefore the largest number were rewarded following the application of generals commanding divisions. For this reason, it was possible that in some cases partiality might occur something which the public might later complain of.

5. Whether any intrigues occurred in his entourage and was he ever aware of them?

Perhaps that was indeed his weakness! Maybe this was due to his noble way of thinking! But it is certain that he sometimes gave way before all those who gloriously commanded in the Polish Legions or who had served with honour in the French army, such as: General [Józef] Zajączek (his greatest and most ardent enemy until his death), [Jan Henryk] Dąbrowski, Sokolnicki, [Aleksander] Rożniecki, Fiszer (equally hostile to him in the early days), and did not reject any of their acts even if they were to the the detriment of officers of greater merit or even those most attached to his person. But who amongst the greatest of men has not been subject to a “but”.

Therefore I, who had the incomparable happiness of being attached to his person for six years; I have the honour of assuring you most solemnly that all those who surrounded him truly loved and respected him from the heart. And that not only do they not resent him in the least for this, but always respecting and glorifying his memory, they will carry with pride to the grave the honour of having been close to a leader of whom it can certainly be said that he lived only for his homeland and died for its glory.

6. At what place in Russia did his fall with the horse occur and was it the fault of the horse or another reason?

I cannot recall exactly the name of the place where the prince fell from his horse [it was on 29 October 1812 at the village of Tsarevo Zaymishtche near Gzhatsk], I only know for sure that this unfortunate incident happened somewhere between Mozhaisk and Vyazma during the retreat [from Moscow]. Being always at the head of the remnants of his corps, he noticed on the left flank of our column, at a distance of few cannon shots, a line of enemy cavalry. Wishing to make a more precise observation, he spurred his huge chestnut English horse, on which he was mounted that day, so as to climb an adjacent hill, but as it was too steep the horse misjudged the distance and fell with all its weight onto the prince so that all of us thought that he had been crushed and killed. When we lifted him up, he could not stand on his feet and for a long time blood trickled from his mouth and nose. Several doctors came at once (but who they were I do not know) and they did so much for him that, after several hours, the blood stopped leaking; even so, a huge bruise remained on one leg, such that he was no longer capable of riding.

7. From where Prince Poniatowski ran his headquarters, when, after being wounded by the fall from his horse, he was unable to command the Poles during the retreat across the Berezina?

After the fall from his horse, a fall which nearly killed him, Prince Poniatowski relinquished command of the remnants of his corps to General Zajączek, and he himself rode in a carriage with his adjutant, Count Artur Potocki, wounded three times during a rather heated battle with the Russians on 5 September, and with the sick Colonel Rautenstrauch. Whereas I, being on the staff of his headquarters, always rode by his side, making the greatest effort to shield him from any danger, and especially from enemy attack, as they were relentlessly pursuing our troops who were then experiencing all kinds of misery, and the enemy did not give us a moment of respite. Leaving Krasnoe, Napoleon himself recommended that the carriage in which the prince rode should follow closely behind the division of Grenadiers of the Guard [the infantry division of the Old Guard commanded by Major-General Philibert Curial]. Later, General [Michel Marie] Claperede’s division, composed of Poles of the Vistula Legion, had the good fortune to watch over the safety of their leader, whose life was dearer to them than all the trophies taken in Moscow and which had also been entrusted to their care.

Having reached the river Berezina on the eve of that most terrible event (and one which no history has ever recorded the like of, or the most vivid human imagination foreseen) the prince’s carriage could not approach the bridge on account of the multitude of obstacles placed before us, and was forced to stand in place for a good half a mile from it and wait long into the night. One can easily imagine my despair which grew with every passing moment, while the prince, rising above all signs of contrary fortune, did not think of himself, but was occupied with the terrible misery of so many unfortunate victims. Already everything seemed lost to me; I had very little hope of saving the dear life of our commander. But, still searching for some unforeseen opportunity, I encountered a detachment of gendarmes of the Guard, who, in response to my most earnest entreaties and being unable to resist the generous reward on offer, came to my assistance, and shouting: ‘Par ordre de l’Empereur!’ they pushed aside all the carriages which clogged the road to the bridge. They overturned some, and destroyed others, in order to leave the road free for the prince’s vehicle. At half past three in the morning the operation was happily completed.

We reached the bivouac of Colonel [Józef] Hornowski, commander of the 17th [sic, the 18th] Infantry Regiment in the division of General Dąbrowski, with much difficulty and he, seeing our need, brought four fresh horses and had them harnessed to the prince’s carriage, and with their help, we continued our journey. And having experienced many more serious hardships and dangers, the details of which are not necessary here, we reached Warsaw in the last days of December.

8. When he arrived in Warsaw after leaving Russia, he is known to have been in charge of completing the shattered regiments. Could you give some account of this until his departure for Kraków and from there abroad?

After returning from Russia to Warsaw, the remaining regiments marched all the way to Kraków much reduced in strength and trickling in, were there augmented with the help of levy en masse, and took on a new organization. The tireless energy of the commander-in-chief and of his subordinates, who followed this example, as well as the desire to work for the common good, and the patriotism of many citizens and civil servants, led in a short space of time to much improvement so that, upon leaving Kraków, the corps amounted to several thousand of the finest and, above all, the most distinguished and reliable troops with a decent number of guns and limbers.

9. Some explanations of his final moments are needed. Did Deschamps or Bleschamps attempt to rescue him from the currents of the Elster river?

Having been sent to the city centre an hour before this unfortunate catastrophe in order to distribute money to the wounded officers, I cannot give much of an explanation about his last moments, but I have great faith in [Hyppolyte] Bleschamps’ self-sacrifice. For who amongst those who had the good fortune to be in his entourage would not have made the sacrifice of his life to save him?

10. Which troops fired on the prince at Leipzig?

I cannot give an account for the reasons given in item 9.

11. Is it true, that after the battle of Leipzig, when the bridge was blown up, he was advised to follow the example of the Saxons, i.e. to put himself and the Poles at the mercy of the Allies, and if so, who dared share such a thought to him?

It is not known to me, if someone, and who that was, advised Prince Poniatowski after the bridge had been blown up, suggesting he surrender himself and the remaining handful of Poles to the discretion of the victors. I can only attest to the fact that when Marshal [Claude] Victor [- Perrin] and General [Mikołaj] Bronikowski [- Oppeln], having left the place entrusted to their defence, were forcing their way through the blocked suburb to the bridge, Bronikowski in this general confusion, having noticed Prince Poniatowski at the head of a handful of Krakus Horse, under the direct command of Captain Roman Puzyna and some cuirassiers under Major [Kazimierz] Dziekoński, approached him. He shared his convinced opinion that everything was already lost and expressed the futility of any further resistance. He tried hard to convince him with earnest entreaties to save himself like the other marshals (Macdonald, Victor) for the sake of the army and for the Poles. Then that immortal man uttered these memorable words (which should remain in the heart and memory of every righteous Pole): ‘God entrusted me with the honour of the Poles, and only to Him shall I return it’.

General Bronikowski, greatly moved by such a response from our hero, did not think any more about his own personal safety, and remained by the prince’s side, sharing the dangers of his last moments and was taken prisoner. If the history of the campaign of 1812 will condemn the memory of Bronikowski, this last act will convince everyone that he could err with his head, but never with his heart.

12. Which of the French marshals or generals did he hold in the highest esteem, either for military talents or for personal qualities?

With regard to both military talents and morals, the Italian Viceroy Eugène Beauharnais was the man most liked and respected by Prince Poniatowski. These two great souls gifted by nature with all the virtues that only mankind can honour, from the first moment of their acquaintance, having understood each other, knew how to respect and love each other until death.

13. From what point of view did Poniatowski judge Napoleon, was it the completely opposite point of view from which Kosciuszko regarded him?

From two points of view Prince Poniatowski considered and judged Napoleon. From the military point of view, he considered him to be a leader whose incomparable genius and might nothing could resist. Politically, however, he was of the opinion that despite the many sacrifices we had made for Napoleon he thought or willed nothing good for us. All hopes of our future existence were based on Napoleon’s unsurpassed ambition to raise the greatness of his state to its highest peak, and thus to extend his rule over the whole of Europe. [Prince Józef] knew however, as well as everyone else, that he would not be able to achieve this unless he waged war with the neighbouring powers of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw. Perhaps in this view he differed from all others, since he based the complete resurrection of our Homeland mostly on the defeat of Russia. In support of this opinion, I can quote the secret instructions he gave, assigning me as a commander of the city of Lwów (Lvov) after our taking of Zamość and Sandomierz and before the arrival of Russian troops there, during the 1809 campaign: ‘Your Lordship; please have the citizens behave calmly, not to interfere in anything, not to get involved in anything, because the happy hour has not yet struck for us. Let them keep that spirit for a better time’.

Further reading: S.K. Bogusławski: Life of Prince Józef Poniatowski. Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Army, Marshal of France [Życie Xiążęcia Jozefa Poniatowskiego, naczelnego wodza woysk polskich, marszałka państwa francuzkiego] Krakow 1831.