Sir William was a widower. But not for long. Emma and Greville’s relationship ended as Greville, perhaps thinking “it is a sad thing if a rich man has no heir to his property”, and differences over the treatment of Emma’s infant daughter, but more likely hungry to acquire a substantial marriage settlement, sought escape. So it was that Greville offered Emma to Sir William. Hamilton demurred, concerned he was too old for the youthful model, and, in a passage which can only be seen as ironic given the events of 1799, replied “It would be fine fun for the young English Travellers to endeavour to cuckold the old Gentleman the Ambassador, and whether they succeeded or not would surely give me uneasiness”.

Sir William was a widower. But not for long. Emma and Greville’s relationship ended as Greville, perhaps thinking “it is a sad thing if a rich man has no heir to his property”, and differences over the treatment of Emma’s infant daughter, but more likely hungry to acquire a substantial marriage settlement, sought escape. So it was that Greville offered Emma to Sir William. Hamilton demurred, concerned he was too old for the youthful model, and, in a passage which can only be seen as ironic given the events of 1799, replied “It would be fine fun for the young English Travellers to endeavour to cuckold the old Gentleman the Ambassador, and whether they succeeded or not would surely give me uneasiness”.

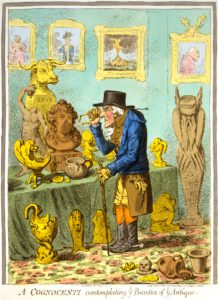

But after gallantly adding that “I do assure you I should like better to live with you both here and see you happy than to have her all to myself for I am sensible I am not a match for so much youth and beauty” he then agreed on the transaction and Emma came out to Naples in 1786, staying, with her mother, at the three-storied Villa Sessa. Many of the visiting British aristocrats luaghed in their silken sleeves, the antiques dealer James Byres, for instance, noted on 14 June 1786 that

“Our friend Sir William is well. He has lately got a piece of modernity from England which I am afraid will fatigue and exhaust him more than all the volcanoes and antiquities in the kingdom of Naples.”

However, she was soon entertaining guests with her artistry, notably her attitudes. Goethe witnessed one of her performances and described her a year after her arrival in Naples in a letter of 16 March 1787:

“an English girl of twenty with a beautiful face and perfect figure. He has had a Greek costume made for her which becomes her extremely. Dressed in this, she lets down her hair and, with a few shawls, gives so much variety to her poses, gestures, expressions, etc., that the spectator can hardly believe his eyes. He sees what thousands of artists would have liked to express realized before him in movements and surprising transformations – standing, kneeling, sitting, reclining, serious, sad, playful, ecstatic, contrite, alluring, threatening, anxious, one pose follows another without a break. She knows how to arrange the folds of her veil to match each mood, and has a hundred ways of turning it into a head-dress. The old knight idolises her and is enthusiastic about everything she does.”

This uncomfortable phase as Hamilton’s mistress was mercifully short, and the couple married in London in 1791 and returned to the social whirl of Naples shortly after. Marriage lent Lady Hamilton nobility, gave her a title, and permitted an improved relationship with Maria Carolina. Emma herself declared “the queen is like a mother to me”, showing her “all sorts of kind and affectionate attentions,” and her proud husband would write that “the queen is quite fond of her and has taken her under his protection”. Even some amongst the waves of English visitors were “remarkably civil” to her. Some, however, enjoyed denigrating the arriviste. From finding fault with her manners:

“Lord Bristol is full of wit and pleasantry. He is a great admirer of Lady Hamilton, and conjured Sr. W. to allow him to call her Emma. That he should admire her beauty and her wonderful attitudes is not singular, but that he should like her society certainly is, as it is impossible to go beyond her in vulgarity and coarseness.”

To belittling her talents:

“Just as she was lying down, with her head reclined upon an Etruscan vase to represent a water-nymph, she exclaimed in her provincial dialect: ‘Don’t be afeard, Sr William, I’ll not crack your joug’.”

Lady Holland found both the Hamilton’s tiresome, confiding in her diary that “The Hamiltons were as tiresome as ever; he as amorous, she as vulgar”. Most concentrated their venom on Lady Hamilton. One of the most hostile of her critics was Charles Lock, who, as consul in Naples, entertained some hope of replacing Sir William at court. He wrote in June 1799 lambasting that “superficial, grasping and vulgar-minded woman” who wished “to retain her husband in a situation his age and disinclination render him unfit for”. Lock became an unflinching foe of the Hamiltons, and of another significant figure in this drama, Nelson.

Nelson was an earlier admirer of Lady Hamilton. He visited in September 1793 as the young captain of the Agamemnon, a little in awe of everyone, and wrote home that Sir William and Lady Hamilton had visited his ship and that “Lady Hamilton has been wonderfully kind and good to Josiah. She is a young woman of amiable manners and who does honour to the station to which she is raised”. Nelson was less impressed with Naples, later writing to Earl of St Vincent “I am very unwell, and the miserable conduct of this Court is not likely to cool my irritable temper. It is a country of fiddlers and poets, whores and scoundrels.”